Brief:

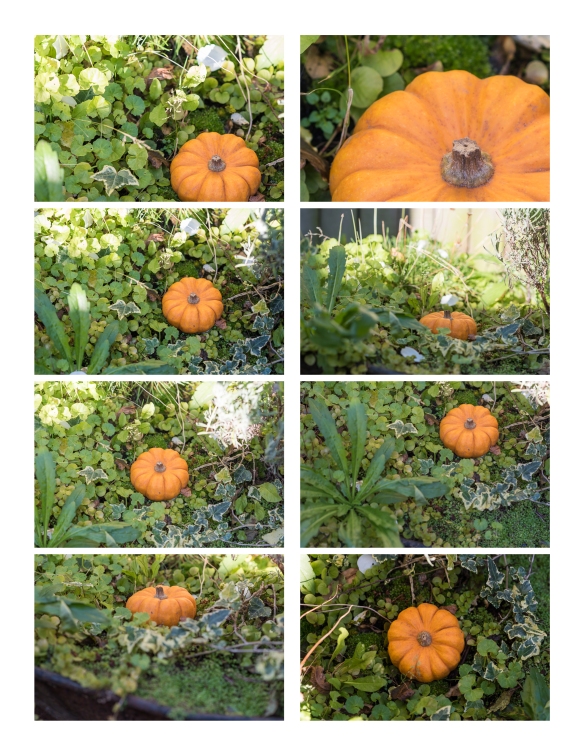

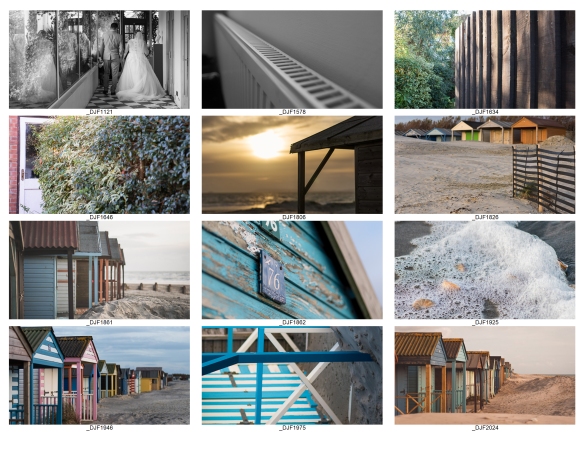

Using the viewfinder grid display in your camera, take a number of shots, composing each shot within a single section of the grid. Ignore the rest of the frame:

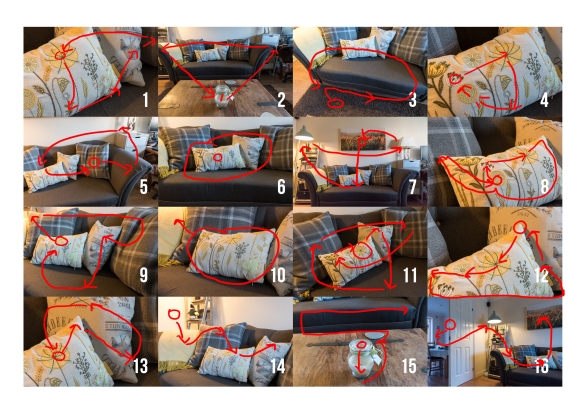

With working full time at this time of year, I have struggled to get out to take photographs during daylight hours, so I decided to take a series of photos for this exercise using the cushions in my lounge.

Framing using small sections of the Viewfinder Grid

view full size images here

In these images, I have used the center of the yellow flower as the focal point for most of the photographs. I have placed them in this grid collage roughly in the area of the viewfinder in which I composed each of the images.

None of the images have been cropped and have had minimal editing.

Technical Information:

Because of low light, I used a camera mounted on a tripod so that I could use a slower shutter speed in order to maintain sharpness and reduce noise. The majority of shots were taken at f/8, except for number 7 (see below), which was taken at f/2.8. Shutter speed was around 1/4 sec or 1/5 sec, ISO 400 and metering set to matrix.

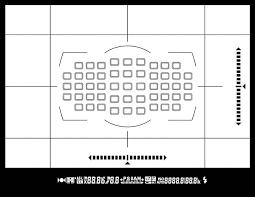

My camera’s viewfinder grid, looks like this

I used the viewfinder and the focus select button to make sure I was focusing in the area of the grid I wanted to compose.

In framing each image I found I was doing more than just moving the ‘point’ around the frame, but was really trying to make a composition within a small part of the screen. I tried to disregard the rest of the frame as directed, which is quite difficult to do, but still produced some surprises when reviewing the images. So I obviously managed to do it.

Image Evaluation:

evaluation of how my eyes travelled around the image

Observations:

- There are both ‘points’ and ‘lines’ in each image.

- The eye isn’t always drawn to the focal point of the image, i.e. No 3

- For images 10, 14 and 16; having only concentrated on the composition in part of the image, areas of distraction have been missed which take the viewers eyes away from the focal point. However, for image 16 this has added a dimension to the story of the picture that none of the others do.

- No 2 has strong lines which take your eyes into and around the image. When I took this I was only looking at the sofa at the top of the image, so was pleasantly surprised by this image.

Reflection:

Trying different areas of the frame to compose the photograph, almost forces you to look at things from different angles and give very different images of the same subject, which makes for more interesting results.

I have used settings that mean that pretty much everything in the frame is in focus. I would like to try this again, using a shallower depth of field to see how this effects the results.

to ‘collections’ in Adobe Lightroom, where a single photograph could be in a number of different collections based on the focus of that particular collection.

to ‘collections’ in Adobe Lightroom, where a single photograph could be in a number of different collections based on the focus of that particular collection.

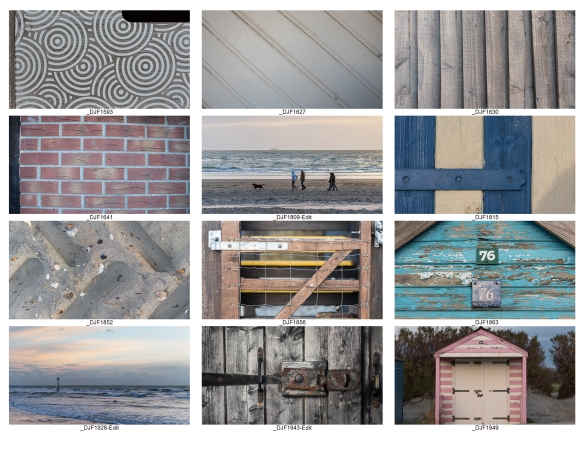

Exercise 1.3 (2) Line

Exercise 1.3 (2) Line Review your shots from both parts of Exercise 1.3. How do the different lines relate

Review your shots from both parts of Exercise 1.3. How do the different lines relate